In the spring of 1910, scientist and entrepreneur Robert-Bénédicte Goldschmidt (1877-1935) invited Spilliaert to immortalise his enormous airship, the Belgique II, on paper. In April 1910, Spilliaert attended a test flight above Auderghem, and based on his sketches, produced some fifteen compositions of the zeppelin and its impressive hangar.

In 1911, Spilliaert exhibited in Paris at Les Indépendants, as did Rik Wouters with whom he spoke about Cézanne. Thanks to a 1912 article by poet Franz Hellens, in the leading journal L'Art moderne, Spilliaert’s name gained some traction. At gallery Georges Giroux, Spilliaert discovered the Italian Futurists. He subsequently exhibited twenty works there himself, along with Permeke and Tytgat, among others. He also exhibited work with the Brussels group Sillon and with Doe Stil Voort.

Henri Vandeputte resurfaced in Paris and asked Spilliaert to join his new project, Les Dessinateurs de Paris. Spilliaert supplied thirty works. In Paris, he also met Verhaeren’s nephew Paul Desmeth, who became a close friend.

Shortly before the First World War, Spilliaert drew many striking compositions featuring one or several fisherwomen, schoolgirls or middle-class women visiting exhibitions, often portrayed with their back to the viewer. He also produced a number of religious compositions based on images of saints and crucifixes.

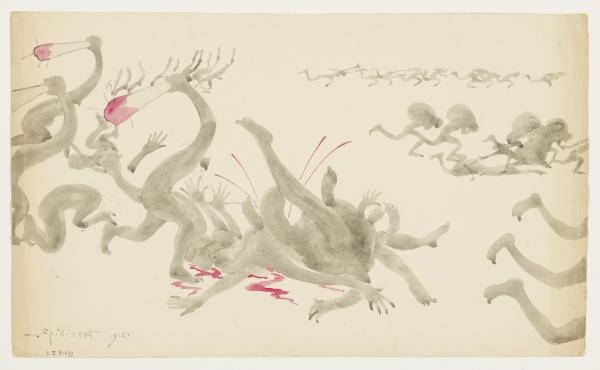

In 1914, the war resulted in many of Spilliaert’s friendships being severed. He himself remained in Ostend, but his mother Léonie and his sister Rachel, like many Belgians, moved to England. There they meet Constant Permeke, who had also ended up on the other side of the Channel. As a civic guard Spilliaert proved to be of little worth: he accidentally took aim at a Belgian soldier. The depressing violence of war also permeated Spilliaert’s work. In 1915, he met his future wife, Rachel Vergison.