There is certainly evidence that Spilliaert had a melancholic side. For example, in 1904, as a young man he did not speak of himself very positively: ‘So many people are put off by my wild, nervous, angry nature and my boorish ways.’1

And in 1920, looking back on his life, he wrote that his childhood was ‘a wonderful memory’, but that his soul had since been ‘stolen’ and he had never managed to recover it. That painful quest was what drove him as an artist.2 He also cultivated the image of the despondent artist in his letters and self-portraits. Moreover, the initially lacklustre response to his art disappointed him.3

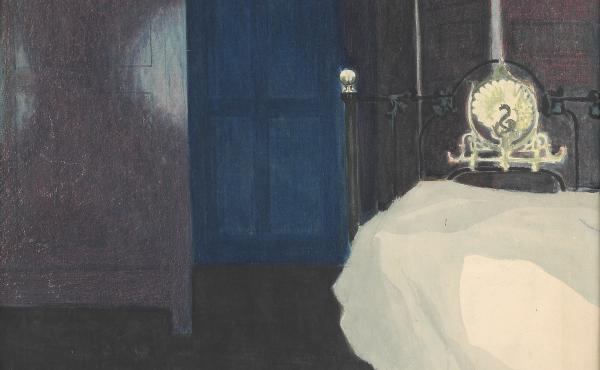

As with many contemporaries, especially those artists linked to Symbolism, much of Spilliaert’s early work is bathed in the decadent decline peculiar to the fin de siècle and literature of the time: Maeterlinck, Nietzsche, and others. The melancholic nature of his works changed in later life, especially after his marriage in 1916, and the birth of his first and only child Madeleine in 1917.

Apart from the fact that he seemed ‘unhappy’, Spilliaert frequently suffered from physical ailments. In the early 20th century, he was regularly plagued by stomach ulcers and in late 1909, he became seriously ill with a life-threatening gastric haemorrhage, and that period of isolation had a lasting impact.4 It might explain why in 1909, in a restless and feverish mood, he wrote: ‘To this day, my life has been lonely and sad, enveloped in coldness.’5 He was tormented by stomach problems his entire life, and his friends and acquaintances often enquired about his health.6 During those periods of illness, his frail physical condition may have stood in the way of real happiness.

But we should not lose sight of the fact that Spilliaert also had a cheery side. His sense of humour and irony not only filtered through to his conversations, but also to many of his works. Consider, for example, the rather caricatural figures he drew: skinny bourgeois men, strange little dogs and fat matrons, followed a little later by running stick men.7 Moreover, in Henri Storck’s short silent film Réunion d'artistes, shortly before his death, we see Spilliaert smiling contentedly in the company of his friends Paul Delvaux and Edgard Tytgat, among others - a very different picture compared to that evoked by the self-portraits forty years earlier.